|

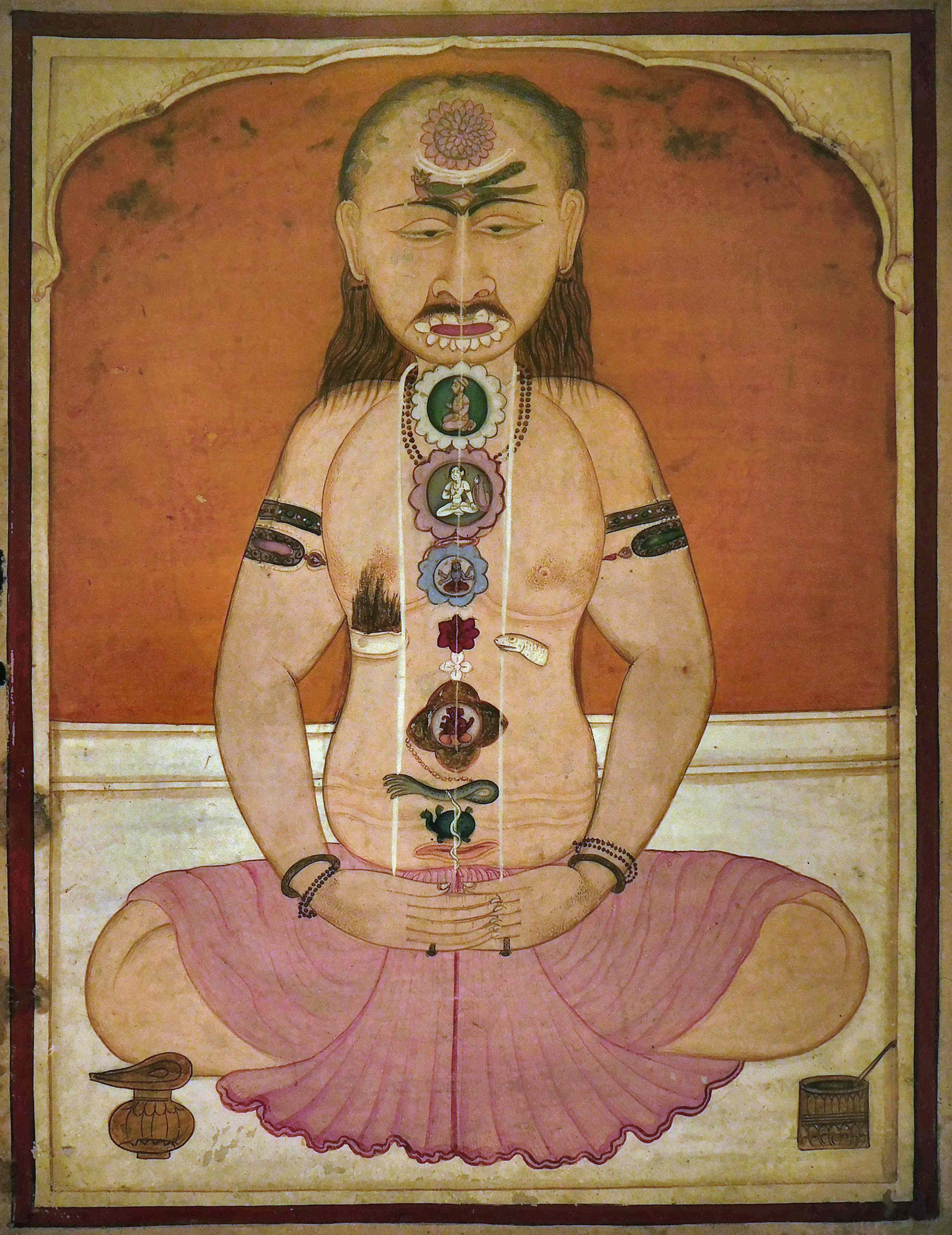

| Yogin in meditation chakras kundalini snake See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Explore the Pancha Koshas — the five sheaths of human existence described in the Taittiriya Upanishad — with a practical, spiritually grounded and science-informed 2,000-word guide.

Learn what each kosha (annamaya, pranamaya, manomaya, vijnanamaya, anandamaya) means, how ancient yogis used this map for spiritual evolution, and how contemporary neuroscience, interoception research and embodied cognition echo these insights.

Table of Contents

-

Introduction — Why the Pancha Koshas matter today

-

Origins: The Taittiriya Upanishad and the idea of sheaths

-

A detailed walkthrough of the five koshas

-

3.1 Annamaya Kosha — the food/physical sheath

-

3.2 Pranamaya Kosha — the vital/energetic sheath

-

3.3 Manomaya Kosha — the mental/sensory sheath

-

3.4 Vijnanamaya Kosha — the intellect/discernment sheath

-

3.5 Anandamaya Kosha — the bliss/causal sheath

-

-

How ancient yogis used the Pancha Kosha model for spiritual practice

-

Purification, practice, and the path of negation (neti-neti)

-

Methods matched to each kosha: asana, pranayama, sense-withdrawal, self-inquiry, samadhi

-

-

Modern science and the sheaths: convergences and translations

-

Neurobiology of body awareness and the Annamaya/Pranamaya layers

-

Interoception, meditation, and the Manomaya/Vijnanamaya layers

-

The neurophenomenology of bliss and the Anandamaya layer

-

-

Practical applications: a kosha-aware practice for modern life

-

Criticisms, limits, and how to use the model responsibly

-

Conclusion

-

References

1. Introduction — Why the Pancha Koshas matter today

The Pancha Koshas (pancha = five, kosha = sheath) are a compact, elegant map of human experience that originated in the Vedantic tradition. Rather than being a metaphysical curiosity, the five-sheath model offers a practical roadmap: start from the gross body and progressively purify finer layers until the innermost reality is revealed.

In the modern era, this ancient taxonomy finds surprising resonance with scientific discoveries about body-mind integration, interoception (internal sensing), and the brain’s role in constructing subjective experience. The result: a time-tested toolkit for holistic well-being that can be read both spiritually and empirically.

2. Origins: The Taittiriya Upanishad and the idea of sheaths

The classical source for the Pancha Koshas is the Taittiriya Upanishad (2.1–2.5), which describes the self as being covered by five sheaths that must be known and transcended to realize the Atman (the Self). The metaphor is simple and powerful: the true Self is like a blade in a scabbard; to see the blade you must remove enclosing layers.

The Upanishadic account arranges the koshas from gross to subtle: Annamaya (food), Pranamaya (vital energy), Manomaya (mind), Vijnanamaya (discernment/knowledge), and Anandamaya (bliss). This structure also maps to three traditional "bodies"—gross (sthula), subtle (suksma), and causal (karana)—helping practitioners situate body, breath, mind and deeper consciousness in a single frame.

3. A detailed walkthrough of the five koshas

3.1 Annamaya Kosha — the food/physical sheath

3.2 Pranamaya Kosha — the vital/energetic sheath

3.3 Manomaya Kosha — the mental/sensory sheath

3.4 Vijnanamaya Kosha — the intellect/discernment sheath

3.5 Anandamaya Kosha — the bliss/causal sheath

4. How ancient yogis used the Pancha Kosha model for spiritual practice

The genius of the Pancha Kosha model is its actionable ordering: begin where you are (your body), then move inward with appropriate tools. Ancient yogis recommended a graduated approach:

-

Clean and strengthen the Annamaya with dietary discipline and asanas so the physical instrument can sit in stillness.

-

Regulate the Pranamaya with pranayama and purification techniques to stabilize energy and create a milieu for refined perception.

-

Calm the Manomaya through sensory withdrawal and mindfulness so the mind’s chatter subsides.

-

Refine the Vijnanamaya by cultivating discrimination and insight; apply reasoning to detect subtle conditioning.

-

Abide in the Anandamaya by surrendering into nondual awareness; from here, the Self reveals itself.

This progression mirrors the classical Vedantic method of neti-neti (not this, not that): each kosha is examined, known, and negated as “not-self” until only the Atman remains. The Pancha Kosha map also guided ethical disciplines (yama/niyama) and practical instructions—giving ancient seekers not only a theory but a precise laboratory for inner work.

5. Modern science and the sheaths: convergences and translations

While the koshas are framed in metaphysical language, modern science offers complementary language and empirical findings that map onto the model. The goal is not to force a one-to-one identity but to show meaningful resonances.

Neurobiology of body awareness: Annamaya & Pranamaya

Contemporary research into interoception (the brain’s sensing of internal bodily states) and autonomic regulation aligns closely with Annamaya and Pranamaya ideas. The brain continually models heart rate, breath, gut sensations and integrates them into a body-schema; therapies that improve interoceptive accuracy (biofeedback, mindful breathing) change physiological regulation and emotional balance.

In yogic terms, pranayama and somatic practices refine exactly this capacity—strengthening the felt sense of the body and stabilizing autonomic rhythms.

Attention, emotion, and the Manomaya & Vijnanamaya

Psychology and cognitive neuroscience distinguish reactive cognition (fast, habitual responses) from reflective cognition (meta-awareness, executive control). Mindfulness and contemplative practices—core tools for the Manomaya and Vijnanamaya—are now well-documented to change attention networks, reduce amygdala reactivity, and enhance prefrontal control.

That is a direct functional analogue of "calming the mind-sheath so that discernment can arise." Multiple empirical reviews show meditation alters functional connectivity patterns associated with both reduced self-referential processing and improved cognitive flexibility.

The neuroscience of bliss: Anandamaya and altered network dynamics

States described as blissful, unitary, or “peak” in modern neurophenomenology often involve reduced activity in the brain’s default mode network (DMN) and altered sensory integration. Such network shifts can produce experiences of self-transcendence that resemble the Upanishadic Anandamaya.

While science cannot (yet) validate metaphysical claims, it can describe reliably that certain sustained practices produce measurable changes in brain dynamics that correlate with profound subjective calm and unity.

Integrative and clinical research linking koshas to health

Recent interdisciplinary papers and reviews are actively exploring the Pancha Kosha model as a conceptual bridge for integrative medicine—helpful in psychotherapy, rehabilitation, and lifestyle medicine because it encourages treating body, breath, mind and deeper well-being as interconnected systems rather than isolated symptoms. This translation is emerging in journals that compare yogic models with neuroscience and clinical outcomes.

6. Practical applications: a kosha-aware practice for modern life

Here is a simple kosha-oriented routine you can use (10–40 minutes total):

-

Annamaya (5–10 min) — Gentle stretching and 5–10 mindful asanas to feel the body; apply nourishment and posture awareness.

-

Pranamaya (3–7 min) — Slow diaphragmatic breathing, 4-4-6 counts, or alternate nostril breathing to stabilize the autonomic state.

-

Manomaya (5–10 min) — Focused-attention meditation: follow breath or a body-scan to calm reactivity.

-

Vijnanamaya (5–10 min) — Short reflective practice: journaling a single insight, or self-inquiry question (Who am I? What is my intention?).

-

Anandamaya (5–10 min) — Rest in silence or open-awareness meditation; notice sensations of ease and the felt quality of presence.

Adapt durations to your schedule. The key is graduated attention: the body first, then breath, then mind, then insight, then repose.

7. Criticisms, limits, and how to use the model responsibly

-

Not literal anatomy. The koshas are phenomenological and symbolic maps—not anatomical charts. Don’t treat them as one-to-one biological entities.

-

Avoid reductionism. While science maps resonances, it should not be used to “explain away” spiritual claims; the kosha model addresses meaning and value as well as function.

-

Cultural humility. The Pancha Kosha comes from a specific cultural and spiritual lineage. Use it respectfully, acknowledging its roots and not stripping it of context.

-

Clinical caution. For therapeutic applications, integrate kosha-informed practices with qualified professionals—especially for trauma or serious mental health issues.

8. Conclusion

The Pancha Koshas are more than a philosophical curiosity: they are a practical toolkit for anyone who wants to work with body, breath, mind and heart in an integrated way. Ancient yogis gave a precise map—start with what you can directly tend (food, posture, breath), then move inward to mental training and finally to contemplative surrender.

Modern science offers convergences: interoception research, meditation neuroscience, and clinical integrative work all point to how bodily regulation, breath control, attention training and reflective insight change lived experience and health. Read together, the koshas and contemporary research produce a powerful, evidence-informed pathway to wellbeing and deeper awareness.

9. References

-

Wikipedia — “Kosha” / Pancha Kosha overview.

-

PubMed Central — Gibson, J.E., “Meditation and interoception: a conceptual framework for ...” (2024).

-

African Journal of Biomedical Research — “Neuroscience and the Pancha Kosha: A Scientific Exploration” (2025).

-

Banaras Hindu University (BHU) PDF — “Concept of Panchakosha in Vedic Literature” (scholarly overview).

-

ResearchGate — review articles linking Ayurveda, kosha model and mental health.

-

Healthline — accessible introduction to the five koshas and practical implications.