|

| Dalma-do(17th century) 김명국(金明國), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}} |

The introduction of Buddhism from India to China stands as one of the most profound cultural and philosophical transmissions in human history.

Over centuries, sutras were translated, doctrines were adapted, and schools flourished, each interpreting the Buddha’s teachings through a uniquely Chinese lens. Yet, no single figure embodies the spirit of this transformative encounter more than the legendary Bodhidharma.

Arriving in China sometime in the 5th or 6th century, he is not merely a patriarch in a lineage; he is a seismic event in the religious landscape.

His teaching, a stark, uncompromising, and revolutionary approach that would crystallize as Chan (later known in Japan as Zen), cut through the burgeoning scholasticism and ritualistic piety of Chinese Buddhism.

Bodhidharma’s legacy is not found in voluminous commentaries but in a direct, wordless transmission of the mind itself—a radical reorientation that defined a new spiritual path and forever altered the soul of East Asian Buddhism.

To understand Bodhidharma’s revolution, one must first appreciate the context into which he arrived. By the time of his purported arrival during the Liu Song and later Liang dynasties, Buddhism was already well-established in China. Schools such as Tiantai and Huayan had developed sophisticated philosophical systems, synthesizing the vast corpus of Buddhist sutras into coherent hierarchies.

Devotional practices, merit-making, and the meticulous study of scriptures were the hallmarks of a mature Buddhist tradition. It was a Buddhism becoming increasingly entangled with imperial patronage and complex metaphysics.

|

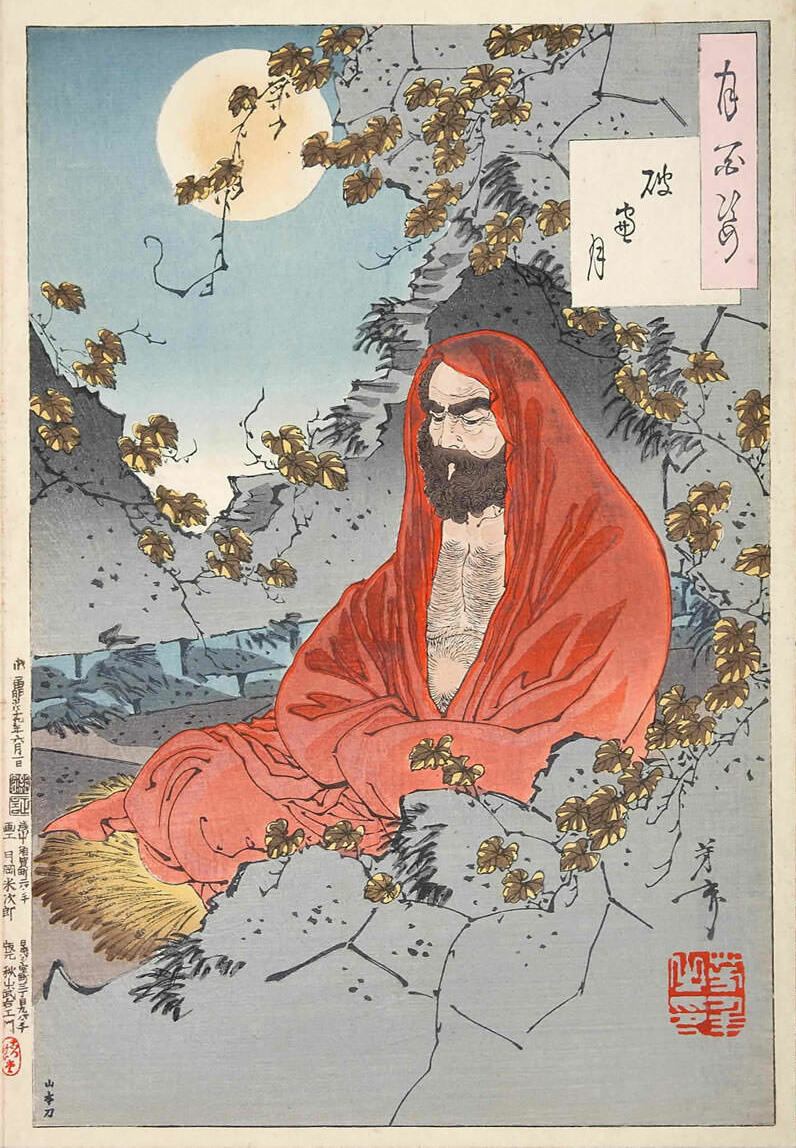

| Bodhidharma, by Yoshitoshi, 1887. Yoshitoshi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}} |

Into this world, the figure of Bodhidharma emerges from the mists of history and legend.

Traditional biographies, composed centuries later, depict him as a formidable South Indian prince of the Brahmin caste who renounced his royal life to become a Buddhist monk.

Acknowledged as the 28th Patriarch in a direct line from the Buddha himself, he is said to have heeded his master's injunction to travel east to China, the "land of the rising sun," where the Dharma was ripe for his particular message.

The legends that surround him—the grueling nine years of wall-gazing meditation in a cave near the Shaolin Monastery, the dramatic interview with the devout Emperor Wu of Liang, and the severing of his own eyelids to avoid falling asleep—are not mere fables. They are archetypal narratives designed to encapsulate the very essence of his teaching.

The encounter with Emperor Wu, immortalized in the Blue Cliff Record and other koan collections, is the foundational myth of Chan. Emperor Wu, a great patron of Buddhism, proudly listed his accomplishments to the enigmatic monk: "I have built many temples, copied countless sutras, and ordained numerous monks. What is my merit?" He expected praise and confirmation of his accrued spiritual capital. Bodhidharma’s devastating reply was, "No merit whatsoever."

With this single phrase, he invalidated the transactional, merit-based spirituality that had become commonplace. He then proclaimed the core of his doctrine: "Vast emptiness, nothing holy." This was not nihilism, but a direct pointing to the absolute, unconstructed nature of reality (śūnyatā) beyond all dualistic concepts of pure and impure, holy and profane.

Stunned, the Emperor asked, "Who is it that stands before me?" Bodhidharma’s final, inscrutable answer, "I do not know," severed the last thread of conceptual grasping, demonstrating a mind utterly free from labels and identity. The interview was a failure in communication but a perfect manifestation of the teaching: a direct shock to the system, designed to awaken rather than to inform.

This distilled essence of Bodhidharma’s teaching is most famously encapsulated in a four-line verse, often cited as his fundamental doctrinal outline:

A special transmission outside the scriptures,Not founded upon words and letters.By pointing directly to [one's] mind,One sees one's own nature and attains Buddhahood.

This tetralemma is the manifesto of the Chan school. Each line is a deliberate and radical departure from the prevailing Buddhist norms of the time.

|

| Dalma-do(17th century) 김명국(金明國), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}} |

Bodhidharma’s practical instructions for achieving this realization are preserved in texts attributed to him, such as the Two Entrances and Four Practices and the Bloodstream Sermon. While their exact authorship is debated, they are universally accepted as conveying the essence of his approach. The "Two Entrances" are the two primary ways of entering the path: the "Entrance by Principle" and the "Entrance by Practice."

The Entrance by Principle is the sudden, direct approach. It involves a profound internal realization that all beings share the same true nature, which is obscured only by "false views and grasping." To enter by principle is to "abide in wall-gazing" (biguan). This term, famously associated with Bodhidharma’s nine years of meditation, is not merely staring at a wall.

It is a metaphor for a mind that is unified, immovable, and undisturbed by external phenomena or internal chatter—a mind like a solid wall, upon which the dust of discrimination cannot cling. It is the practice of non-duality, where subject and object dissolve, and one rests in the unshakable conviction of one's inherent Buddha-nature.

The Entrance by Practice provides a behavioral and attitudinal framework for those not yet capable of such a sudden leap. It consists of four adaptable practices for navigating life's circumstances:

Requiting Hatred: Accepting suffering and adversity without resentment, understanding that it is the karmic consequence of one's own past actions. This transforms hardship into a path of liberation.

Following Conditions: Remaining unmoved by the vicissitudes of life—gain and loss, praise and slander—understanding that all phenomena are dependent on conditions and are inherently empty.

Seeking Nothing: The most radical of the practices, it involves abandoning the "craving mind" that constantly seeks something—be it worldly goods or even spiritual attainment. As the text states, "The wise are always content with things as they are."

Accordance with the Dharma: Practicing the perception of the essential emptiness of all things, free from the duality of self and other, thus aligning one's every action with the ultimate truth.

These "entrances" are not mutually exclusive; they represent the sudden realization of truth and its gradual embodiment in daily life. Together, they form a complete path: a direct insight into mind-nature, supported by a resilient and equanimous way of being in the world.

Bodhidharma’s impact was not immediately widespread. He was a marginal figure, a radical teacher whose uncompromising message found only a few receptive ears. His most important disciple was Huike, who, in another defining legend, stood in the snow outside Bodhidharma’s cave and cut off his own arm to demonstrate his sincere and desperate seeking of the Dharma. Huike became the Second Patriarch, and through him, the lineage was passed down through Sengcan, Daoxin, and Hongren, eventually culminating in the Sixth Patriarch, Huineng, whose platform sutra would democratize and popularize Chan, cementing Bodhidharma’s legacy.

The long-term impact of Bodhidharma’s teaching on Chinese culture and beyond is immeasurable. The Chan school he inspired became one of the most influential forms of Buddhism in East Asia. Its emphasis on direct experience over textual scholasticism resonated deeply with native Chinese Daoist sensibilities, particularly its appreciation for spontaneity, naturalness, and non-conceptual wisdom. This synthesis gave birth to a unique aesthetic that permeated Chinese and later Japanese culture, evident in the minimalist elegance of ink-wash painting, the stark beauty of rock gardens, the spontaneous art of calligraphy, and the profound simplicity of poetry.

Furthermore, his association with the Shaolin Monastery, whether historical or legendary, forged an indelible link between spiritual cultivation and physical discipline. The image of Bodhidharma practicing intense meditation to strengthen his body and mind laid the groundwork for the development of Shaolin Kung Fu, creating a tradition where the training of the body was seen as an integral part of mastering the mind—a manifestation of the unity of principle and practice.

Perhaps Bodhidharma’s most enduring legacy is his demystification of Buddhism. By locating Buddhahood squarely within the human mind, he made enlightenment immanent and accessible. He shifted the focus from pious devotion and complex metaphysics to the simple, yet profoundly difficult, task of self-knowledge. He taught that nirvana is not a distant paradise but the nature of this very mind, and samsara is the state of being deluded about that simple fact. His methods, later refined by his successors into the use of koans (gong'an) and "dialogues of the way" (wenda), were designed to shatter the logical mind and provoke a direct intuition of reality.

In conclusion, Bodhidharma’s teaching in China was a radical return to the existential core of the Buddhist quest. In an age of increasing institutionalization and intellectualism, he served as a powerful corrective, a "barbarian from the West" who reminded China that the Dharma is not a subject for scholarship but a fire to be kindled in the heart.

His message—that truth is beyond words, that it is within us, and that it can be seen directly—was as simple as it was profound. The legendary, unblinking gaze of Bodhidharma, facing a wall for nine years, is the perfect symbol of his teaching: a relentless, unwavering attention turned not outward toward scriptures or deities, but inward toward the very source of consciousness itself. He did not bring a new sutra; he brought a mirror. And in that mirror, he urged all of China, and eventually the world, to look directly and see the face they had before their parents were born—the original face of the Buddha.

Boddhisatva's message—that truth is beyond words

ReplyDeleteNice comment. Thanks. Visit again.

ReplyDelete